Everything you know about the movement against the Vietnam War is wrong

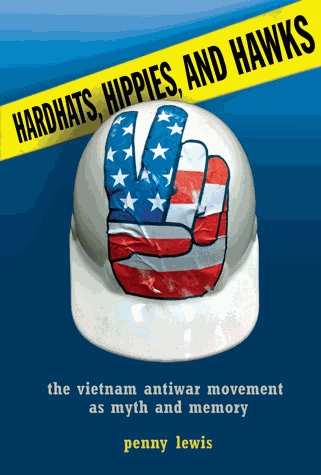

Penny Lewis, a sociologist at CUNY’s Murphy Institute for Worker Education and Labor Studies, has a new book out: Hardhats, Hippies, and Hawks: The Vietnam Antiwar Movement as Myth and Memory.

It’s a revisionist account of the movement against the Vietnam War that completely upends our sense of who was for and against the war. Even more interesting, it tells us how we came to such an upside down view of the antiwar movement.

Luckily I don’t have to summarize the book because Penny’s got a terrific piece out in this week’s Chronicle of Higher Education where she lays out the argument.

Just a quick excerpt:

The story we tell ourselves about social division over the war in Vietnam follows a particular, class-specific outline: The war “split the country” between “doves” and “hawks.” The “doves,” most often conflated with “the movement,” were upper-middle-class in their composition and politics. The movement was the New Left, and a big part of what made the New Left “new” was its break from the working-class politics and roots of the Old Left. Think of Dr. Benjamin Spock, Tom Hayden, Jane Fonda, Eugene McCarthy, George McGovern, Students for a Democratic Society, Weathermen: students, intellectuals, professionals, celebrities; liberal or radical privileged elites.

And what of the “hawks”? Beyond the military brass, war supporters are often imagined as “ordinary” Americans: white people from Middle America (a term coined in the 1960s), who supported God, country, and “our boys in the ‘Nam.” They were working-class patriots who insisted that criticism of the war meant criticism of the soldier. “If you can’t be with them, be for them,” as the sign read. Many of these Middle Americans epitomized moderate middle-class solidity and stolidity, while the workers among them, or members of the lower middle class, are remembered for having supported George Wallace and Richard Nixon, and their status as Reagan Democrats was imminent, even immanent, as early as 1968.

Most accounts of the working class depict them as largely supportive of the war and hostile to the numerous movements for social change. We need look no further than the most enduring image of the working class from that period, a certain cranky worker from Queens, N.Y. The TV character Archie Bunker, who brought the working class to prime time as white, bigoted, sexist, homophobic, and yearning for the good old days before the welfare state, when everybody pulled his weight, when girls were girls and men were men.

“Hardhats,” a stereotype based primarily on construction workers in New York City who assaulted antiwar protesters at a Manhattan rally in May 1970, were the iconic hawks. The most important working-class institution in the postwar era, the AFL-CIO, is remembered for being virulently anticommunist and vociferously pro-war; big labor’s embrace of the Vietnam cause confirmed the image of the working-class patriot who shouts “Love it or leave it!” at young, entitled hippies.

But this memory of the Vietnam era contains only half-truths, and overall it is a falsehood. The notion that liberal elites dominated the antiwar movement has served to obfuscate a more complex story. Working-class opposition to the war was significantly more widespread than is remembered, and parts of the movement found roots in working-class communities and politics.

In fact, by and large, the greatest support for the war came from the privileged elite, despite the visible dissension of a minority of its leaders and youth. The country was divided over the war, alongside many other pressing social issues—but the class dynamics of those divisions were complex, contradictory, and indeterminate.

Many books briefly discuss the discrepancy between our historical impression of class-based sentiment and its reality. Yet no account systematically explains why such a misperception exists, its extent, or its impact.

So read Penny’s piece. And then go buy her book. Trust me: you won’t regret it.