Next time someone tells you the Nazis were anti-capitalist…

h/t Suresh Naidu

Update (5 pm)

On Twitter, Justin Paulson brought this fascinating article from The Journal of Economic Perspectives to my attention. It’s called “The Coining of ‘Privatization’ and Germany’s National Socialist Party.” Apparently, the first use of the word “privatization” (or “reprivatization”) in English occurred in the 1930s, in the context of explaining economic policy in the Third Reich. Indeed, the English word was formulated as a translation of the German word “Reprivatisierung,” which had itself been newly minted under the Third Reich.

.

27 Comments

-

William Neil April 20, 2014 at 4:44 pm | #

Thanks Corey. And a parallel line of reasoning, and comparison to actual events would be the claim by many on today’s American Right, especially Rush Limbaugh, that Hitler was a “socialist.”

The actual facts, after some deft feints and big lies, unfolded from May Day, May 1st, 1933, after Hitler had been elected and proceeded to consolidate power. In his May Day speech of that year, “he proclaimed an end to the class war that had impaired the national spirit, so that from then on all Germans, ‘the brain workers and fist workers,’ would be united in their labor under the leadership of National Socialism for the good of the people and the state. The following morning the meaning of these words became clear: units of the SA and the SS seized the offices, homes, clubs and banks owned by the socialist trade unions and most of their leaders and many of their active members were arrested, disappearing into prisons and concentration camps. The unions, with their 4.5 million members, were disbanded…A week later, on May 10, Hitler mounted his assault of the Social Democratic party. Throughout Germany the Nazi rulers seized the party’s offices, funds and more than a hundred of its newspapers….On June 22 the Social Democratic party itself was officially banned. It was not necessary for Hitler to move against the bourgeois parties which included his Conservative partners: they disintegrated and folded on their own initiative.”

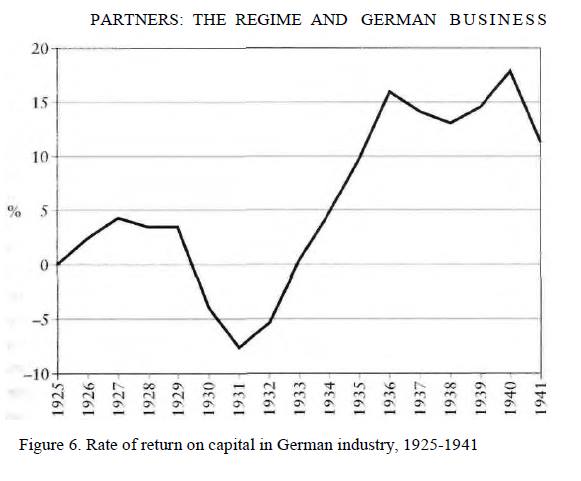

Now what is my source for these quotes, these straightforward recitations of events as they unfolded in historical and actual sequence, preceding the rise of business profits revealed in your chart above? The source is the book by Leni Yahil, “The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry,” published in 1990 by the Oxford University Press, pages 57-58.

When Rush Limbaugh began making his Obama-socialist- Hitler was a socialist claims I send the same quotations to some of our professional historian organizations, the most famous one, asking them to publicly refute Limbaugh’s assertions. They replied that they didn’t take “political stands.” I told them I was most certainly not asking for a political stand, but a factual one backed up by a clarification of what happened in Germany (before and after 1933): that socialists and social democrats, not to mention communist party members were systematically rounded up and their institutions destroyed. So much for professional historical organizations.

-

Joanna Bujes April 20, 2014 at 6:18 pm | #

Just recently I read somewhere that fascism is what happens when markets fail….and there is no organized revolutionary movement.

-

Jara Handala April 22, 2014 at 10:47 am | #

1) To aid descriptive & explanatory attempts it’s important to have a typology of political entities & their causes, & we need to recognise the necessary differences between what is reactionary, authoritarian, dictatorial, & fascist. The ‘f’ is bandied about as a pejorative, & not only does this have the ‘Peter who cried wolf’ effect, but it also obfuscates, impairing understanding, & crucially for those under the cosh it impairs how to combat what one is suffering.

What was distinctive about the political movements headed by Mussolini & Hitler was that they succeeded after failed massive mobilisations by the workers’ organisations in those countries. That’s a necessary quality of a fascist regime in being a natural social kind rather than simply being the referent of a phrase (& so nominalist rather than real).

2) You say “when markets fail” but what is ordinal for managers & owners of firms (& by extension, state managers) are structural problems with capital accumulation, manifesting as a profitability crisis. This contrasts with markets because they are a distributional means (of what has been produced), but the societal problem originates in production. Market behaviour is derivative of production behaviour, so by comparison it is epiphenomenal of that which is causally more powerful.

And this links with my first point: the structural problem is largely a consequence of the organised strength of workers, in the workplace & electorally. Hence the political opportunity for a movement intent on destroying, no exaggeration, workers’ organisations – their unions, their cultural societies, their political parties. Cometh the moment, cometh the fascist movement to save civilisation from the barbarians. Better black than red, if not, better dead than red.

‘Markets failing’ is an ambiguous phrase, furthermore one rooted in the discourse of the post-1870 marginalist reconceptualisation of economic activity, an attempt to put to one side the inquiry called political economy. The enduring achievement of the latter has been to insist upon examining the relationship between economic groups, & the apportioning of the surplus product, the excess over what’s needed for subsistence. By contrast the marginalists focused not on surplus but scarcity, & hence their focus was not on the relations between economic groups but between people & the things they desire. It has been an attempt to focus on individuals, sometimes aggregated as groups, & to refuse to conceptualise social entities such as classes.

(I’ve made a comment below, citing Alfred Sohn-Rethel, on the relationship between the Nazi movement, their anti-capitalist dimension, & big German firms.)

-

-

Roquentin April 20, 2014 at 6:22 pm | #

It’s not so simple as that. There was a degree of socialism in national socialism, at least prior to the Night of the Long Knives. I’d argue that they were perhaps center-left and represented an attempt by many formerly royalist politicians to give up just enough so as hold off a communist revolution. There was a lot of effort in terms of propaganda made to graft anger towards capitalism in Weimar Germany onto racial hatred aimed at Jews. I know when this argument is typically made, it is made by the likes of Rush Limbaugh who want to make everyone believe that anything except for hardcore American nationalism = mass graves. In spite of that, painting the European far right as a neoliberal capitalist outfit is neither productive nor accurate.

You can see some of this even today in parties like the National Front in France. People in the US again and again make the mistake of believing the political divisions everywhere else in the world are exactly like they are here, as if the same issues get thrown in the same buckets. It’s not true. I think parties like the National Front are the most direct modern descendants of European right, anti-capitalist, racist(now phrased in the more benign sounding rhetoric of “anti-immigration”), and nationalist. It doesn’t work that way. Ideologies are a pastiche specific to a time and situation, and trying to cram everything into the lens of US political divisions is pure folly.

-

Corey Robin April 20, 2014 at 6:27 pm | #

At the level of propaganda, you’re right. At the level of policy, though, the anti-capitalist rhetoric seldom found a corollary. A lot of the government spending that was supposedly workerist was absorbed in rearmament. There’s no doubt that fascism was meant to absorb the energies of the socialist left, but again, it was mostly at the level of propaganda rather than policy.

-

Roquentin April 20, 2014 at 6:43 pm | #

On this point I would agree. In general, that was a large part of the motivation for why the Night of the Long Knives occurred. There were factions of the party which took the “socialism” of national socialism seriously (Strasser and Rohm) and expected some degree of reform, but when this was never delivered on they were purged from the party. That and Hitler wanted the support of the traditional German army, which considered the SA to be a group of street thugs, at least if I remember it correctly.

There is also debate to be had about at which point you separate the propaganda of a party from what policies it acts on when in power. It’s hard to argue that there was no hostility towards capitalism within national socialism or fascism (not exactly the same thing either as I tend to associate that term more with the political program of Mussolini).

-

Jara Handala April 22, 2014 at 8:57 pm | #

An informative eye-witness source on the relationship of the Nazi Party in government to big business is Alfred Sohn-Rethel’s Economy & Class Structure of German Fascism, CSE Books (London), 1978, 159 pages. (CSE is Conference of Socialist Economists.) No-one, as far as I know, has called him a participant-observer but he was indeed the exemplar of a traditional ethnographer.

A graduate of Heidelberg University & friend of Ernst Bloch & Teddy Adorno, he was not surprisingly a Marxist but through a family friend he was able to infiltrate the web of capital, working 1931-6 at the HQ of the German big business association lobbying for an eastwards expansion, Mitteleuropäischer Wirtschaftstag (Central European Economic Forum), writing & editing weekly newsletters for it & similar organisations in Berlin.

Some comments have spoken of how the Nazis were antagonistic to the prevailing capitalist society. It must be stressed that the anti-capitalist behaviour was only of some of the Nazis & it was purely discursive, more accurately towards big firms. As said in the thread, Röhm & the SA, 3 million strong, were the Nazis who advocated the socialist worker fork of the NSDAP, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, & they wanted a ‘second revolution’.

Having successfully destroyed workers’ organisations they then wanted a revolution against the aristocrats & the ‘fat cats’, the banksters of the day, the ostentatious quality ably depicted in the New Objectivity images of George Grosz & Otto Dix. This desire had already been on show in February 1934 in Austria. The dictator there, Engelbert Dolfuss, had banned the Austrian fascist party (DNSAP, yes, it was an anagram but preceded its German imitator), & when widespread fighting broke out between state forces & workers the DNSAP called for neutrality but many of its members & supporters fought alongside social democrats & communists. (This mirrored the picket lines in German labour disputes, 1929-32, jointly manned by Nazis & communists, the ‘Third Period’ of the Communist International when social democrats were deemed the left-wing of fascism.)

The SA also wanted to form the core, at all levels, of a new army for the New Order which obviously motivated the miltary bureaucracy to appeal to Hitler. This accelerated Hitler’s move against the SA which was carefully planned & executed in the days starting 30 June 1934.

Sohn-Rethel fled to England in 1937 & became a high school teacher of French. He also wrote on coinage, arguing that as the means allowing non-barter exchange it was the abstract reality encouraging the development of abstract thought, as found in the flourishing of early Greek culture; he is also noted for his work on the separation of mental & physical labour. At the age of 73 he became a prof in Germany of social philosophy, no mean achievement, & a just recognition of his worth. (I believe Tooze, the source of Corey’s graph, cites Sohn-Rethel’s book.)

http://www-user.uni-bremen.de/~steglich/This is a painting of the man, by Kurt Schwitters, whilst they were interned by the Brits as if they were Japanese:

http://www.epdlp.com/fotos/schwitters4.jpg

-

-

-

BillR April 20, 2014 at 8:38 pm | #

“He who does not wish to speak of capitalism should also be silent about fascism”.

– T.W. Adorno

-

John Weickhardt April 20, 2014 at 9:41 pm | #

Thanks for this graph, but it is largely a pic. of the Great Depression.

It would be interesting to see the USA “Rate of return on Capital” superimposed on it. -

Bob Kircher April 20, 2014 at 10:23 pm | #

According to Tapley the Brown-Harriman-Bush investments supported international German/Nazi business positions before and after WWII began and after the US had officially entered the war. The US govt brought “trading with the enemy act” charges against these parties and seized certain of their assets. Eventually, there was little to no penalty for any of these charges against the parties due to key witnesses suddenly found dead days prior to hearing dates and or mysteriously disappeared witnesses before essential testimony and evidence gathering events were publicly scheduled. All on record. Like so much of of essential American history buried in the archives.

-

Jim Brash April 20, 2014 at 11:03 pm | #

Its always been my understanding that the Nazis ruled because the German bourgeoisie couldn’t. They may have had anti-capitalist propaganda but their official policies were always anti-labor.I don’t think that they ever nationalized an industry or expropriated any capitalist unless they happened to be Jewish or Slavic. There was no necessity to do so.

-

David Chuter April 21, 2014 at 5:13 am | #

I don’t think this graph tells us anything, really, other than that the German economy recovered massively after 1933, under the stimuli of rearmament, infrastructure investment and the reintroduction of conscription. You’d get essentially the same picture if you graphed the precipitous fall in unemployment and poverty that took place at the same time.

The Nazis were pragmatists, who were not interested in conventional economic policy questions, and simply wanted to create a war economy capable of an exterminatory campaign in the East, to carve out the living space their racial theories said they deserved. Hitler made his peace with the Army and the traditional political establishment by forcibly disbanding the SA and cracking down on the genuine radicals like the Black Front, because he needed them. He made his peace with the bankers and industrialists because he needed their help. He even made his peace with the Catholic Church because he recognised that there was no point in multiplying enemies needlessly. But none of these decisions represented a political orientation for its own sake.

Attempts to shoe-horn the Nazis into conventional left-right distinctions, especially as used today, are pointless. They have their origin in the fact that the Nazis, with their minority but useful tally of seats in the Reichstag, were courted by the traditional Right to join the government, and, of course, outwitted their tempters terribly. But for the Nazis this was only ever a means to an end. They were, if anything, a right-wing radical populist nationalist movement, drawing support from the economic misery of the times, and the sense of national humiliation felt by most Germans after 1919. The idea of the Nazis as the shock-troops of capital (very common in my youth), was essentially the Marxist reading, which has lost a lot of its popularity today.

Because Nazi ideas were based on race, and were essentially outside the traditional left-right spectrum, they were the sworn enemies of forces of the Left (socialists and communists) who operated on a class-based, as opposed to racial, interpretation of society, and were internationalists rather than nationalists. Such ideas, the Nazis believed, could only fragment the German national community, and make the triumph of the Slavic hordes easier. These parties had therefore to be destroyed at all costs, as did trades unions, which weakened national unity by pitting the classes against each other, and so made the country vulnerable.-

William Neil April 21, 2014 at 10:25 am | #

David:

My quick retort to you would be that the left shouldn’t take the Nazi movement too personally, as aimed at them due to left-right ideological hostility; no, the organized left was wiped out (it’s leadership and institutions, at any rate, the rank and file were needed for the militarized racial crusades) for reasons of nationalist mobilization and racial living room in the East. Feel much better now.

Let’s go back to the days before Hitler was elected in 1933, and destroyed what was left of Weimar’s democratic political institutions. The Nazis were busy conducting a war in the streets, and winning against the left for years before they came to power. Political assassinations were common. What was the reaction of the German state, its police and court system? They largely stood down and let it happen. The leaders of German industry reached an early accommodation with Hitler, as did the military, and not until the war’s catastrophic outcomes for Germany were clear after 1943 did elements of the ruling class try to assassinate him. And the German middle classes, who could not accept any form of the left, which was largely an urban power in Germany…but weak everywhere else, what did they do? They went Right in the elections; it may have been with a strong streak of populism, I think that is a fair part of your observation…but when you add up all these elements by 1934, the left had been wiped out, the Right triumphant, the leading business leaders and institutions tolerant of Hitler if not outright enthused, and the middle class following their lead, with new jobs and rising incomes, didn’t have to worry about left-labor troubles.

Are you carrying the racial aspect too far? The Slavic threat to the East was a communist Soviet Union, with active, subversive ties to communists inside Germany, so was it the racial antagonism or the class based challenge to the whole economic order in Germany more important?

I think Chris Hedges is making the point this morning at Truthdig, in his regular Monday morning space, that when vigilante violence in the US rises, it is often deployed on the part of the economic Right, whatever other emotional and racial streams feed into it, and there were other streams in the Klan’s formulations in the 1920’s: anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant…those southeastern Europeans, you know…

I would be interested to know what you think of the Cliven Bundy standoff with the US government in Nevada, which I think the left ignores at its own peril. Does not the armed Right in the US, which makes the federal government its chief rationale for arming, do so for the very same reasons that old Mr. Calhoun of S.C. turned to nullification, secession and state’s rights, that the mere gesture of a powerful federal government in domestic and economic affairs threatens the economic Right…imagine that, trying to collect leasing fees; where will it stop? As others have pointed out, the armed Right militias didn’t show up at Occupy Wall Street in NY to protect them…or bristle in the directions of stock exchange…populist? A right leaning populism.

-

David Chuter April 21, 2014 at 4:00 pm | #

William,

I mostly agree, though I do think it’s dangerous to try to analyse what happened in a quite short and utterly unique period of time through the prism of conventional political distinctions today. It’s also important not to confuse those who voted for the Nazis in the relatively free elections of 1930 and 1932 (not much more than a third, in spite of some intimidation) with the general accommodation to Nazism after January 1933 when Hitler became Chancellor. In fact, even in 1930 the Social Democrats were still the largest party. Moderate reformers, they shared the political landscape with the Communists, who stood for revolutionary change, and a group of mainly traditionalist right-wing parties, some nostalgic for the Empire. The Nazis (on about 3%) were generally seen as a rather nasty joke. Even in 1932, you would have to say that, on a conventional left-right analysis, the combined vote of the Left (SPD and KPD) was about the same as that of the Nazis.

But its arguable that in times of political and economic crisis, the real distinction is less left-right than traditional-radical. German parties were effectively divided at the time between parties like the SPD and the Centre Party, which wanted to work within the system, and the radicals like the Nazis and the KPD who wanted to destroy it. One way of interpreting the 1932 results is as a clear majority for those who wanted to destroy the Weimar Republic (about 60% including some small parties). In practice, the Left was not necessarily against capitalism, nor the Right always in favor of it.

It’s not clear that those who voted for the Nazis consciously wanted all this: they essentially registered the most calamitous protest vote in history. The traditional Right thought they could keep the system going by co-opting into government the naive and uncouth Nazis, the largest single party in the Reichstag, as they had used the Nazis to fight the threat from the Communists, as you say. The Nazis used the naivety of the traditional Right to get into power and destroy the system totally. How far the populist rhetoric of the Nazis actually influenced voting, I don’t think even specialists are sure.

I think the point about elites and rank and file is important. Leaders of the KPD and SPD were killed or driven into exile, but the rank and file were regarded as “good German blood” and so capable of being “rescued” from the delusions of communism and socialism. Indeed, the repentant Communist is a standard figure in Nazi propaganda films, if I remember correctly. This also links to the question of how the Soviet Union was viewed: as with similar paranoid regimes, I’m not sure the Nazi leadership was itself capable of distinguishing between the Slavic Hordes and the Red Menace.

In the end, the Nazis were radicals in that they totally transformed Germany in a way that the traditional Right would never have done. They were popular for many years because their main initiatives (ending unemployment, abrogating the Versailles Treaty) were widely popular across the political spectrum, rather than being left-right issues.

I don’t know enough about the US to sensibly comment on recent events there, but, if you accept the above analysis, it is clear that proponents of radical solutions do not always come from the Left: in Europe today they come from the radical Right, and their “populism” actually addresses many themes which the Left abandoned a long time ago. This could all get very nasty.-

William Neil April 21, 2014 at 4:59 pm | #

David:

I gave away my copy of Franz Neumann’s “Behemoth” years ago, and it never found its way back to my library. Surely there must be copies and fluent readers somewhere in the NY City vicinity. If so, please chime in.

I’ll have to make do with Peter Fritzsche’s “Rehearsals for Fascism: Populism and Political Mobilization in Weimar Germany,” 1990, Oxford U. Press. .

It makes grim reading, based on intensive studies of voting and political activity in one area of Northern Germany, Lower Saxony between 1918-1930. Here is a passage from the conclusion, on how the Nazis, the middle classes, and the left saw each other during Weimar:

“With resolution and vigilance, they (the Nazi party) opposed the socialist Left. Even more aggressively than the Stahlhelm (a street active veterans group), the National Socialist paramilitary force, the SA, challenged its Social Democratic and Communist counterparts. Streets, taverns, and meeting halls became bloody arenas for political fights. In neighborhoods across Germany, National Socialists gained widespread recognition for their active and public confrontation with the Left. Burghers saw in the Nazi movement what they believed to be the strategic advantages of the socialists, namely organization, resolve, and fanaticism. They tolerated the ‘excesses’ and violence of the brownshirts before 1933 because these were also considered the sins of the Left. The poison determined the antidote. Thus the Nazis can be seen as one of the most accurate representations of how bourgeois Germany regarded the socialists. Home guards, burgher leagues, the Stahlhelm – the Nazis were only the most recent creature of the chauvinistic and visceral antisocialism of the German Burgertum.”

-

-

-

-

Roquentin April 21, 2014 at 10:04 pm | #

I’m reminded a bit in this discussion of Berlin Alexanderplatz, which while fictional is also a great insider’s account of life in Weimar Germany. I’m only familiar with the Fassbinder adaptation of it, but the episode in which Bieberkopf is fresh out of prison, desperate for work, and ends up selling Volkischer Beobacther newspapers was particularly insightful. I’m sure Alfred Doblin, as a German Jew, could see the writing on the wall in 1929.

-

Hilary Huebsch April 23, 2014 at 3:30 pm | #

See also Norbert Ehrenfreund’s “The Nurnberg Legacy” which discussed all 13 trials, not just the famous one of the High Command, and includes a chapter on how the Krupp Case affected Big Business. Highly recommend this book.

-

Bill Thompson August 3, 2014 at 1:06 pm | #

“We are socialists, we are enemies of today’s capitalistic economic system for the exploitation of the economically weak, with its unfair salaries, with its unseemly evaluation of a human being according to wealth and property instead of responsibility and performance, and we are all determined to destroy this system under all conditions.” –Adolf Hitler

-

William Neil August 3, 2014 at 5:40 pm | #

“The truth is, we are all caught in a great economic system which is heartless.”

Woodrow Wilson

Taken from Richard Hofstadter’s “The American Political Tradition,” (1948), The quote is the epigraph for Chapter X, “Woodrow Wilson, The Conservative as Liberal.”

The quote is actually taken from Wilson’s book, “The New Freedom,” published in 1913, which in turn is a collection of his speeches from the great campaign of 1912.

-